The Two Distinct Shoulder Muscle Functions

1 – Stability

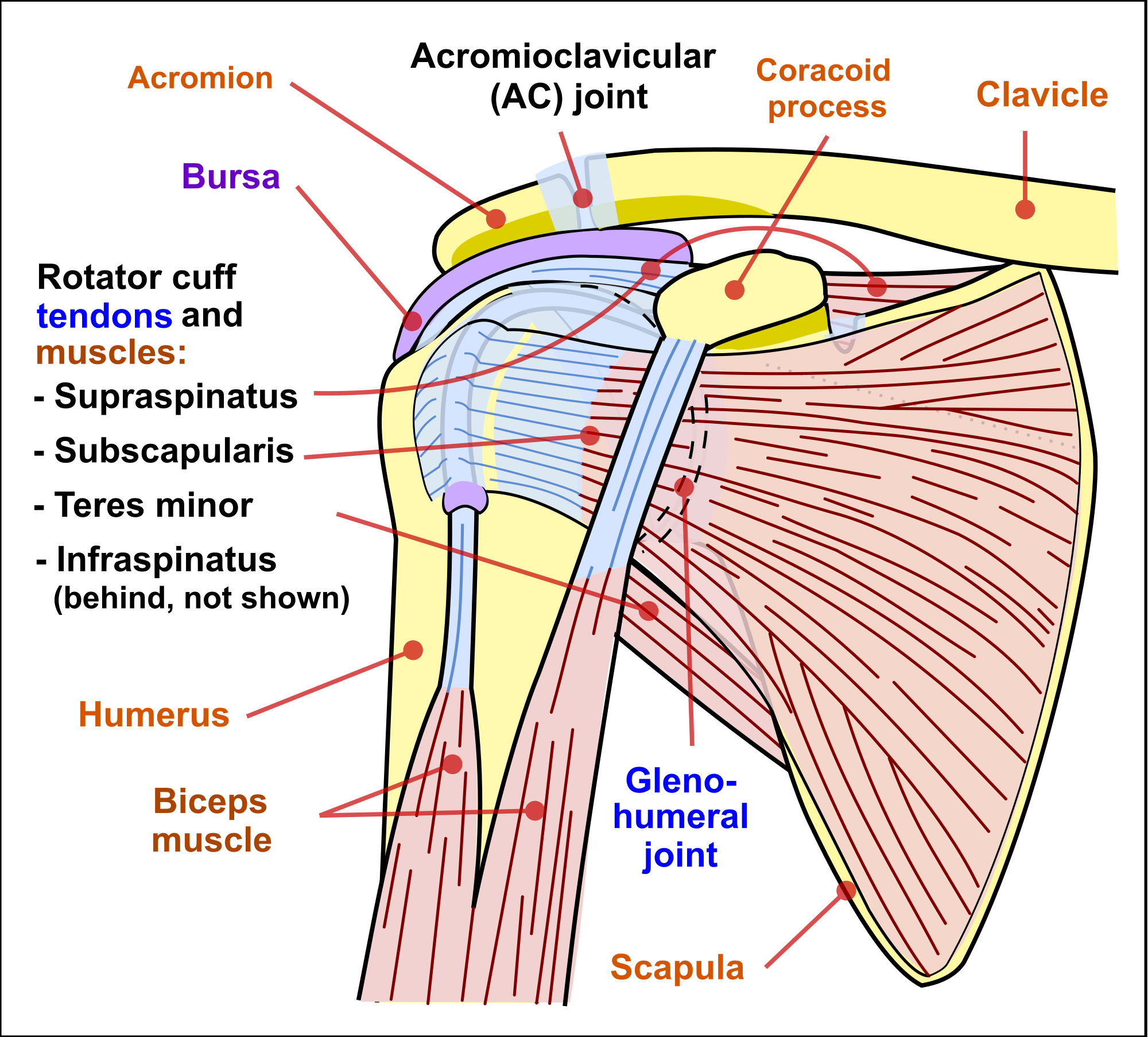

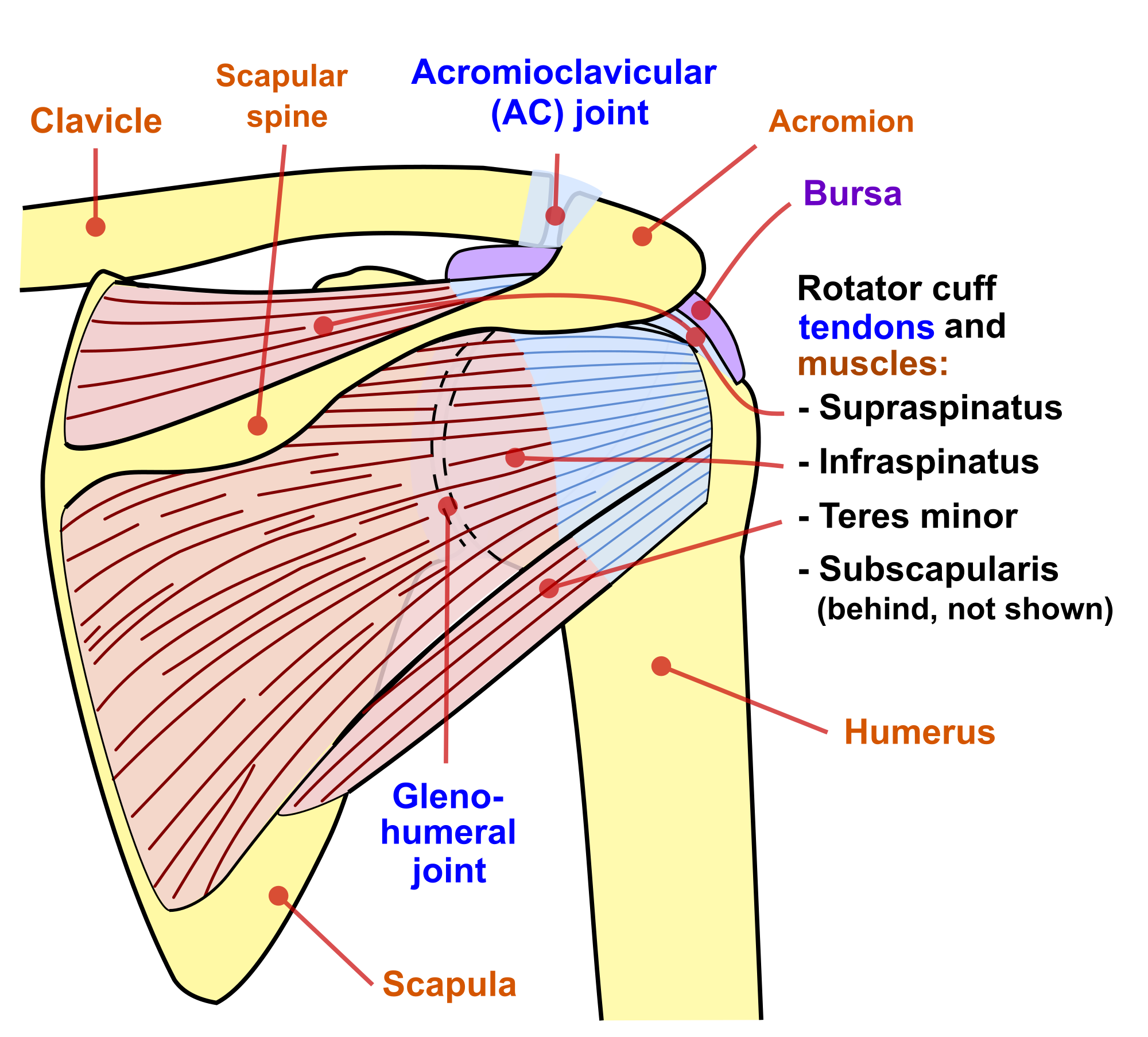

Before we deep dive into the muscles that control and support our shoulder movement, we need to understand why some of them are there in the first place. Especially the rotator cuff muscles. In the previous part about the shoulder ligaments and the capsule, we demonstrated that the shoulder cannot be stabilised by the ligamentous structure alone. Therefore, another structure is needed to ensure the shoulder doesn’t dislocate. We mentioned there were mechanoreceptors to sense when the shoulder starts to become more unstable. It is the muscles that are activated by the CNS in response to the sensors’ activity to compress and stabilise the shoulder joint. These muscles together form the rotator cuff. The rotator cuff muscles are composed of:

- Subscapularis

- Supraspinatus

- Infraspinatus

- Teres Minor

2 – Motion

The primary function of the rotator cuff muscles is to increase the stability of the glenohumeral joint. However, the primary function of muscles, in general, is to provide a means to move your body. There are various muscles that span your shoulder and are involved in its motion. The list below shows the role of each major muscle group:

- Subscapularis – Internally rotates the humerus (upper arm), and acts to adduct (lower) your arm when it is raised [1].

- Supraspinatus – Acts to abduct (raise) the upper arm [2].

- Infraspinatus – Acts to externally rotate the upper arm [3].

- Teres minor – Also acts to externally rotate the upper arm [4].

- Deltoid – This large muscle group has four major functions: i) Forward flexion (raising your arm out in front), ii) internal rotation of the upper arm and iii) Abduction (raising your arm our by your side) and iv) external rotation of the upper arm [5].

- Bicep (long head) – Help press the humeral head into the glenoid adding to the stability [6].

- Trapezius – More commonly known as ‘Traps’. Acts to steady the shoulder by controlling the elevation, depression, rotation, and retraction of the scapula [7].

- Rhomboids – The group together act to retract the scapula. They also work alongside the levator scapulae to help rotate the scapula such that the socket faces more downward.

- Levator scapulae – As the name suggests, the primary function of this muscle is to elevate the scapula [8].

- Teres major – Primarily acts to adduct and internally rotate the arm [9].

- Serratus anterior – Protracts the scapula. Commonly referred to as the ‘big-swing’ or the ‘boxer’s’ muscle [10].

- Choracobrachilais – Helps flex and adduct the arm [11].

3 – What Could Go Wrong?

If one muscle does not act properly, this could lead to an unstable shoulder. An example of this would be rotator cuff tear or weakness. The stabilising muscles cannot contract or produce a force large enough to ensure the socket stays intact. But a rotator cuff tear may not necessarily just lead to an unstable shoulder. The muscles are also responsible for ensuring the motion of the shoulder is efficient. A tear could lead the ball of the socket, the humerus, to migrate during motion and cause subacromial impingement. The problems and pains can become much worse if more than one muscle does not act as they should. This is because the shoulder muscles work together to achieve both stability and the desired motion efficiently. Another example is that of the scapula stabilising muscles. Those muscles that control the scapula are directly responsible for the position of the scapula relative to the thorax. This means that the slightest of problems, the smallest of muscle knots can lead to an abnormal scapula position and/or motion. This can have a knock on affect on other muscles and cause chronic pain in the neck, the upper arm etc,

4 – What Can You Do to Prevent Such Problems?

One the most recommended acts is to exercise the muscles in and around the shoulder regularly. This does not mean heavy weight training in the gym, but simple motions as in this post here can help a lot. However, we recommend that you book a free session with us and use our devices. We are sure that you will experience the benefits immediately which is unlike any other shoulder exercise you could possibly do.

Conclusion

This is the final part of the 3 part series on the anatomy of the shoulder joint. We hope that this has provided some insight into the complexities of the joint, an overview of how the joint works and how easy it is for something to go wrong. The purpose is to educate so that those of you who are reading this and are not performing your prescribed exercises, have a change of heart and do what is necessary to improve and get better.